The model includes both state and month fixed effects. The state fixed effects, in particular, adjust for all time-constant factors, including a state's membership to the treatment group. Note that you defined $TREAT$ as equal to 1 if a state is in the treatment group, 0 otherwise. By its very definition, a state's treatment status doesn't change over time. A state is either in one of two groups: the treatment group or the control group. Time-invariant "group membership" is already accounted for by the inclusion of state fixed effects.

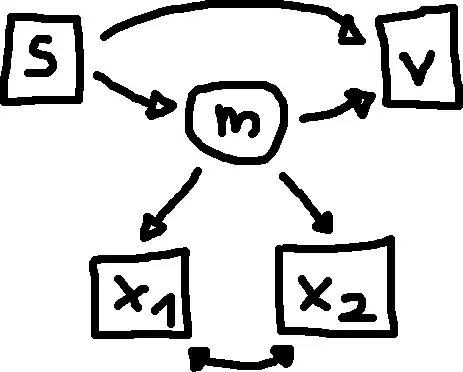

You could actually specify your equation more simply given that the "timing" of the policy (i.e., treatment) is standardized among treated states, at least this is the case using a monthly time frequency. The classical difference-in-differences equation looks like the following:

$$

y_{st} = \alpha + \sigma T_s + \lambda A_t + \delta (T_s \times A_t) + u_{st}

$$

where you observe outcome $y$ in state $s$ in month $t$. $T_s$ is equal to 1 if a state is in the treatment group, 0 otherwise. This is the same as $TREAT$ in your earlier equation. $A_t$ is a time dummy equal to 1 in the months after treatment in both groups, 0 otherwise. The product of these two terms returns the difference-in-differences estimate.

The generalization of this equation regresses $y_{st}$ on a full set of state effects, a full set of month effects, and a treatment indicator. Here is the basic two-way fixed effects equation:

$$

y_{st} = \sigma_s + \lambda_t + \delta D_{st} + u_{st}

$$

where the parameters $\sigma_s$ and $\lambda_t$ denote fixed effects for states and months, respectively. A quick word with respect to the month fixed effects. To be precise, the model requires a variable denoting all months—not a repeating sequence of say, months 1–12. In other words, if you have 15 months, then you need a variable that uniquely delineates all 15 periods. $D_{st}$ is the interaction term just defined in a different way (i.e., $D_{st} = T_s \times P_t$). In most applications, $D_{st}$ is a dichotomous policy variable indexing when a policy 'turns on' (i.e., switches from 0 to 1) in state $s$ by month $t$, 0 otherwise.

In your second model, it appears you want to interact $T_s$ with a series of month indicators. Here is one of the many ways to specify your equation:

$$

y_{st} = \sigma_s + \lambda_t + \delta^{k} (T_s \times M^{k}_{t}) + u_{st},

$$

where $M^{k}_{t}$ represents a series of month dummies for the $k$ periods before and after treatment. Note how the constituent elements of the product term don't appear in this equation. The individual main effects are redundant with the state and month fixed effects. What's important in this setting is the interactions of $T_s$ with the month dummies; these coefficients remain. Let's see this in action.

To begin, I augmented your panel a bit. If we used the abridged data frame included in your post, we don't have enough residual degrees of freedom to estimate dynamic treatment effects. To make this work in practice, I "lengthened" your panel. Now we have 3 states observed over a 9-month period. I also simulated new $y$-values. Here is the result of emp_clean:

## Augmented data frame

# N x T = 27

# 3 states

# 9 months

# Alabama is treated

# California and Louisiana serve as controls

# The treatment is adopted uniformly in month 13 onward

## Variables

# delstat = unit (state) identifier

# period = time (month) indicator

# emp = outcome

# treat = treatment indicator

# after = post-treatment indicator

# policy = policy dummy (treat x after)

# A tibble: 27 × 6

delstat period emp treat after policy

<fct> <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 Alabama 8 4.59 1 0 0

2 Alabama 9 4.96 1 0 0

3 Alabama 10 5.83 1 0 0

4 Alabama 11 5.23 1 0 0

5 Alabama 12 5.22 1 0 0

6 Alabama 13 9.97 1 1 1

7 Alabama 14 10.0 1 1 1

8 Alabama 15 9.85 1 1 1

9 Alabama 16 9.95 1 1 1

10 Louisiana 8 4.32 0 0 0

11 Louisiana 9 5.13 0 0 0

12 Louisiana 10 5.19 0 0 0

13 Louisiana 11 4.33 0 0 0

14 Louisiana 12 4.36 0 0 0

15 Louisiana 13 5.46 0 1 0

16 Louisiana 14 5.39 0 1 0

17 Louisiana 15 4.56 0 1 0

18 Louisiana 16 4.72 0 1 0

19 California 8 4.95 0 0 0

20 California 9 7.28 0 0 0

21 California 10 7.01 0 0 0

22 California 11 2.53 0 0 0

23 California 12 5.29 0 0 0

24 California 13 4.77 0 1 0

25 California 14 3.92 0 1 0

26 California 15 3.15 0 1 0

27 California 16 4.07 0 1 0

Now that we have some data to work with, let's quickly review a base R solution. Note that your policy uniformly affects all states in the same month. In other words, treatment timing is the same across all states. If this is truly the case, then the two equations specified below should produce equivalent estimates of the treatment effect.

## Model 1 - Classical DiD (2x2)

lm(emp ~ treat*after, data = emp_clean)

## Model 2 - Generalized DiD (Multiple Groups/Time Periods)

lm(emp ~ policy + as.factor(delstat) + as.factor(period), data = emp_clean)

Now let's estimate some models using the fixest package. If you don't want any redundancies, simply include the policy variable on the left-hand side of the |. Here is the basic structure:

feols(emp ~ policy | delstat + period, data = emp_clean)

Collinearity should be non-existent, assuming you created the policy variable appropriately. On the other hand, including the interaction term directly (i.e., treat*after) before the | works as well, but R warns you that the constituent elements of the product term are collinear with the fixed effects. R is actually doing the right thing; it's dropping the redundant terms for you without any additional work on your part. Here's the summary output:

OLS estimation, Dep. Var.: emp

Observations: 27

Fixed-effects: delstat: 3, period: 9

Standard-errors: Clustered (delstat)

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

policy 5.325 0.962008 5.5353 0.031122 *

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

RMSE: 0.678526 Adj. R2: 0.806451

Within R2: 0.771657

The coefficient on policy should be similar to the estimates using lm().

The next equation is estimating dynamic treatment effects. The feols() function allows you to easily specify a reference period. I assume the twelfth period is the month immediately before the treatment goes into effect. In most applications, it's quite common to omit the period before policy adoption. Here is the basic structure:

feols(emp ~ i(treat, period, ref = 12) | delstat + period, data = emp_clean)

This is typically referred to as an "event study" model. The name is quite fitting, as we're trying to exploit some "event" of interest. In the pre-policy periods, the confidence intervals associated with each interaction should bound zero. Here's the summary output:

OLS estimation, Dep. Var.: emp

Observations: 27

Fixed-effects: delstat: 3, period: 9

Standard-errors: Clustered (delstat)

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

treat:period::8 -0.442994 0.206997 -2.140100 0.165703

treat:period::9 -1.645000 0.848225 -1.939300 0.192019

treat:period::10 -0.663947 0.620491 -1.070000 0.396622

treat:period::11 1.403200 1.903700 0.737071 0.537818

treat:period::13 4.460200 1.135900 3.926700 0.059160 .

treat:period::14 4.998100 1.668700 2.995200 0.095729 .

treat:period::15 5.603500 1.628100 3.441700 0.075042 .

treat:period::16 5.159200 1.098100 4.698100 0.042442 *

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

RMSE: 0.567197 Adj. R2: 0.746413

Within R2: 0.84044

Indeed, it's correct to call the estimates in the pre-policy epoch "placebo" effects/coefficients. We are deliberately defining the periods before the event as the actual treatment periods. In essence, these are "fake" treatments. We shouldn't be observing the effects of a state-wide policy/law emerge before it's actually enacted! All the action should be concentrated in the post-policy epoch. I artificially simulated values to show you this, but your results could look quite different in practice. In your post, your tabular results suggest a delayed policy effect, but it's hard to say without acquiring more data beyond August.

In short, you should only concern yourself with the coefficients on the interaction terms. Including $TREAT$, by itself, has no effect on your point estimates. Time-invariant state-level attributes are collinear with the state fixed effects. Even if you did include $TREAT$, R will safely exclude it.