This is a great question that is subtlely different from the usual "what is the difference between A♭ and G♯?" Apart from frequency differences in non-12-et tunings, that question relates to the function of the note within the chord/scale/key.

But if we're talking about choice of key, then there are other factors at work. Obviously in non-12-et tunings, the choice of A♭ major vs G♯ major does have to do with how it will sound. But let's assume 12-et for the rest of this answer.

There are three general factors that, I would have thought (but see below about Bach), led a composer in the common practice era to choose one key over another enharmonic one:

- avoid double sharps and double flats in the key signature itself

- reduce double sharps and double flats in the keys to be modulated to

- reduce double sharps and double flats in the keys used by transposed instruments

As others have mentioned, the Well-Tempered Clavier is interesting here. The point of the piece was to demonstrate the 12-major and 12-minor keys on an instrument where enharmonic notes have the same frequency. So frequency-wise there really can only be 12 major keys.

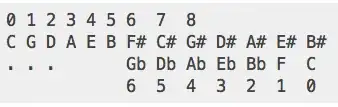

But from a naming point of view (assuming you wouldn't be as crazy as to have double sharps or double flats in your tonic) you have 21 possible key names for each of major and minor.

How would one go about choosing which 12 key names out of 21 to use? First step might be to avoid double sharps and double flats in the key signature itself. Note that the result is different between major and minor keys (as WTC demonstrates). That reduces your choice from 21 to 15 (so G♯ D♯ A♯ E♯ B♯ F♭ majors are out)

Then it likely just comes down to what you're going to modulate too. If you are going to modulate to V, you might want to avoid having to introduce the double-sharp to do so (which means C♯ major is out). If you are going to modulate to V of V, then F♯ might be out too).

All that said, it makes it particular interesting that WTC does use C♯ major and F♯ major and instead eschews D♭ G♭ C♭ to get from 15 possibilities to 12. The C♯ major prelude and fugue does indeed need a double-sharp in modulated passages, even though the note is diatonic.

In the case of ensemble pieces with transposing instruments: imagine a clarinet part in concert C♯ major :-)